City Council Looks at Road Safety Concerns on Franklin Street and Citywide

By Ellen Putnam

DPW Workers installing Rapid Rectangular Flashing Beacons at a crosswalk on Main Street

Photo Credit: Nancy Clover

This week, the City Council heard from city officials about what the city is doing to address road safety concerns, particularly on Franklin Street.

The Franklin Street corridor, from Main Street down into Stoneham, is an area of concern for many residents and has seen multiple crashes in the last few months. In January, resident Elliott Garlock posted on social media about a crash at Franklin and Ashland Streets and shared several examples of collisions in that immediate area over the last few years. He concluded, “If Melrose doesn't change, there's going to be a dead person (maybe a dead child) because of the current policy.”

Garlock's post generated community discussion about traffic safety in the Franklin Street area and prompted three city councilors to call for city officials to share what safety measures can be taken there and in other parts of the city that face similar challenges. And just last weekend, a driver hit a utility pole and power was lost in sections of the neighborhood for hours following.

Mayor Jen Grigoraitis, Department of Public Works (DPW) Director Elena Proakis Ellis, and Melrose Police Chief Kevin Faller all came before the City Council in their most recent meeting to answer questions about street safety.

Ten members of the public, including two representatives from the Melrose Pedestrian and Bicyclist Committee (Ped-Bike) spoke for over 40 minutes during the public comment period, sharing concerns about the safety of the area around Franklin, Ashland, and West Highland Streets in particular, but also about West Wyoming Avenue and the Lynn Fells Parkway.

“The situation at Ashland and West Highland has gotten ridiculous,” said one resident, “Drivers are showing blatant disregard for the stop sign.”

“We’re at a point where somebody’s going to get killed,” said another.

Collision at Franklin and Ashland Streets in January

Photo Credit: Elliot Garlock

Ward 1 Councilor Manjula Karamcheti, who was among the councilors who had called for the hearing, shared, “The safety of vulnerable road users is the number one issue my Ward 1 constituents raise. We must take immediate and comprehensive action and collaborate on a clear and actionable plan to move forward.”

Councilor-At-Large Ryan Williams, who is involved with the Ped-Bike Committee and also asked for the hearing, added, “If you’ve been outside your car in Melrose for more than a few minutes, you’ve experienced these issues. And we’re not alone in these experiences: they’re happening to every other city and town. There’s good work being done here, and being done elsewhere, also on tight budgets. I’m hoping this meeting will serve as a kind of launchpad for the conversations we need to have as we move into the Vision Zero future for Melrose.”

Vision Zero is a nationwide traffic safety initiative that aims to eliminate all traffic-related fatalities and serious injuries. The main idea behind Vision Zero is that drivers and other road users “will sometimes make mistakes, so the road system and related policies should be designed to ensure those inevitable mistakes do not result in severe injuries or fatalities.” This is different from many other approaches to traffic safety in that it focuses less on drivers as individual actors and more on the overall system.

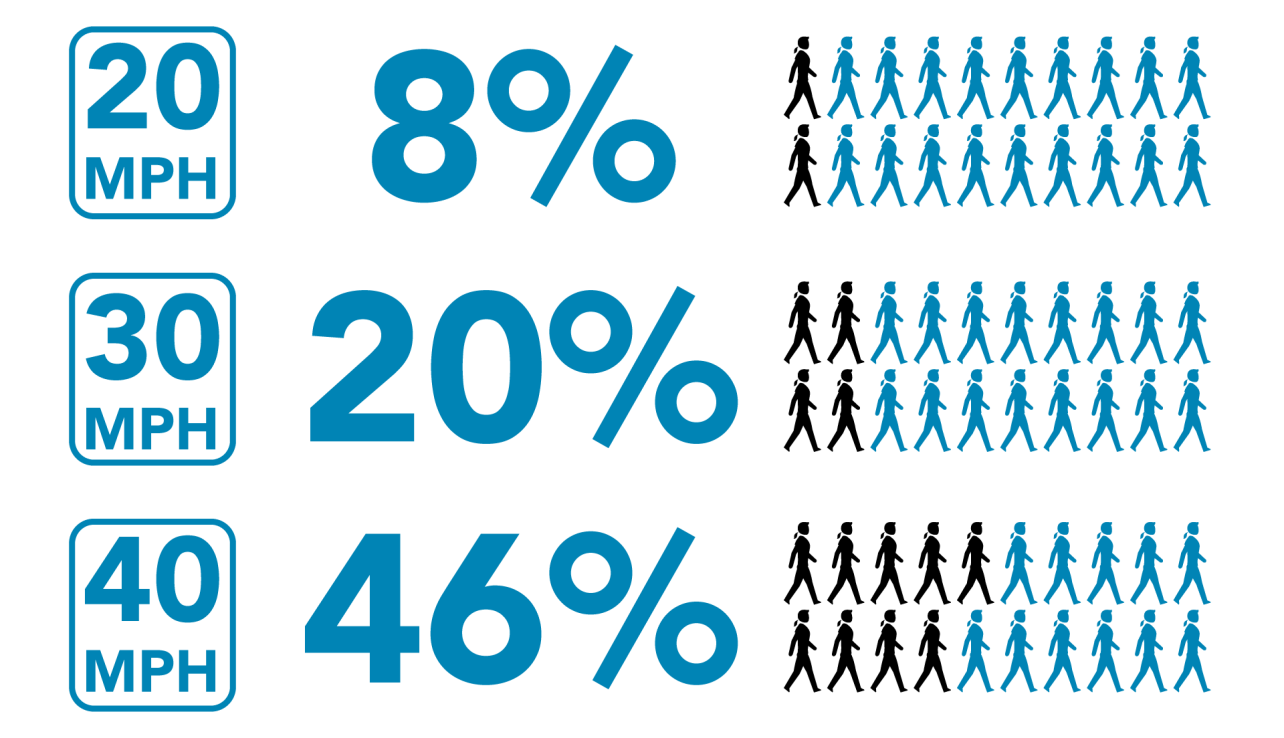

The faster a car is traveling, the more likely it is a collision will be fatal for a pedestrian

One of the key ideas behind Vision Zero is that even small increases in a car’s speed can have potentially deadly consequences. A collision between a pedestrian and a car traveling at 20 miles per hour has an 8% chance of being deadly; that same collision, if the car is traveling at 40 miles per hour, has a 46% chance of resulting in a fatality. Vision Zero communities often set lower citywide speed limits, and they intentionally narrow roadways and add traffic calming devices such as speed bumps to make it difficult for drivers to exceed speed limits.

Mayor Grigoraitis included Vision Zero in her campaign platform, and she has announced that she will be forming a Vision Zero Task Force, which she hopes to have the City Council make into a permanent city commission.

“Everyone in this room agrees that there is more work to do, and we are eager and excited to do it,” said Grigoraitis. “I do think there is also a very important conversation to be had about our level of resources that we have to put before this.”

From left to right: DPW Director Elena Proakis Ellis, Police Chief Kevin Faller, and Mayor Jen Grigoraitis, at this week's meeting

Screenshot from MMTV

“We do not have anyone on the infrastructure side of the DPW who is even part-time dedicated to traffic calming,” she went on, “That is just not how we are structured as a department. This is done as part of full-time jobs that already exist, and that staffing is going to get more challenging” with the departure of City Engineer Vonnie Reis who, Grigoraitis said, “has really been the lead on a lot of these projects.” The opening she leaves behind will likely not be filled due to the city’s current budget shortfall.

There is a traffic supervisor within the Melrose Police Department, but each shift only has three patrol cars on the street at a time. “We certainly hear the requests for more enforcement,” said Grigoraitis, “but the reality is, without additional resources, we are static in the number of people who can write tickets, who are available.”

“I think we have done a lot with a very stagnant, and frankly a shrinking pool of resources available to us,” Grigoraitis added.

Governor Maura Healey has proposed allowing traffic cameras to be used for speed enforcement, which is currently prohibited in Massachusetts. If the state legislature approves the measure as part of this year’s state budget, it would allow Melrose to deploy five speed cameras at key locations throughout the city.

The City of Melrose adopted a Complete Streets policy in 2016, which is focused on making road improvements that benefit all users, including to sidewalks, crosswalks, and bike lanes. Since then, said DPW Director Ellis, the Complete Streets policy “has been the guiding principle for every project we do.”

Photo Credit: Nancy Clover

Some of the improvements the DPW has made on projects throughout the city in recent years include:

- reconfiguring parking to make crosswalks more visible;

- adding Rectangular Rapid Flashing Beacons (RRFBs) to crosswalk signs;

- narrowing travel lanes to discourage speeding;

- adding speed feedback signs to encourage drivers to follow the speed limit;

- and reconfiguring or narrowing intersections to force cars to slow down when entering the intersection.

“Every time we’re doing a capital project, we try to improve all those things,” said Ellis. “When we’re moving through the city, we try to make those kinds of improvements every time we touch a street.”

“We’re kind of in a constant state of trying things and adding things,” Ellis went on, “We just keep doing little things, but the reality is, there will always be people who are driving too fast. A lot of the people driving in Melrose are people who live in Melrose - so they’re driving safely on their own street and speeding on everybody else’s street and then complaining that everyone is driving too fast. It’s an issue everywhere, and it’s really hard to solve, but we’ll keep chipping away at it.”

On Franklin Street specifically, Ellis said, “we’ve done a ton in the last decade in the interest of traffic calming and safety,” including adding and improving crosswalks at several points, which she said “has definitely slowed speeds.” The DPW performed traffic studies at the intersections of Franklin Street with Vinton Street and Greenwood Street, and found that neither location qualified for adding a traffic signal. They plan to add a few more crosswalk beacons along Franklin Street but otherwise, Ellis went on, “any future initiatives would come out of the Vision Zero process.”

Franklin Street

The city’s plans for the Vision Zero process are still, according to the mayor, dependent on a number of external factors, including a $100,000 Safe Streets for All federal grant the city received through the Metropolitan Planning Organization for crash analysis. “Putting in speed bumps might slow traffic,” said Ellis, “but it doesn’t tell you if you will mitigate fatality and serious injury crashes. The goal of the initial Vision Zero analysis is to figure out the root cause of crashes. We need data before we can come up with solutions.”

City Councilor Kim Vandiver asked if volunteers on a Vision Zero Task Force could get started on some of that work without waiting for an outside consultant.

Grigoraitis responded: “Like most things in government, we move too fast for some people and too slow for others. I recognize there is a group of people who would like to see us, ‘go, go, go.’ We’re thrilled we’re going to get this $100k - hopefully. It’s federal funding so I think there’s an open question about the long-term viability of that money under this current administration. We want to wait to understand the grant, and we want to make sure we’re not doing work that’s going to put us in jeopardy of not being able to leverage that funding.”

But some members of the Ped-Bike Committee disagree that solutions need to wait for the federal funding and resulting crash analysis. “Not only should the city not wait to do everything they can to slow down cars right now,” said Lani Nelson, Chair of the Ped-Bike Committee, during public comment, “but I don’t think we need to do studies upon studies measuring the speed of cars to find out that people are going too fast. There are things that can be done with quick actions that don’t require studies and consultants and finally, in five years, there will be a permanent speed hump on Franklin Street. There needs to be something that’s done before then, because somebody will die or get seriously injured.”

Residents are concerned that new developments like The Ella, currently under construction, may add to foot and car traffic in the area. Developers can also contribute to streetscape improvements.

“This is an issue that cuts across basically everyone in the entire community,” added Ped-Bike member Finn McSweeney. “We all know we are a community whose resources do not match its ambitions of what we think we can be, but establishing a Vision Zero policy commitment for the community helps with all of the little decisions that we’re always making, every day, every month, every year along the way. It’s not something that necessarily needs to be accompanied by a funding source,” he went on, noting that in addition to providing guidance for upcoming projects, a Vision Zero policy could make use of funding sources like the streetscape improvement fund, which developers of large projects already pay into.

The Ped-Bike Committee recently released a set of Vision Zero Action Plan Recommendations that they hope will help guide the city’s Vision Zero process. The recommendations encompass community engagement, design, and enforcement. The design section of the plan includes improving intersections; implementing both quick-build and permanent traffic calming improvements in school zones, commercial districts, and residential neighborhoods; building safer mid-block crosswalks; and creating a bike network that is accessible to all ages and ability levels.

Councilor Vandiver asked whether residents could do some streetscape improvements themselves, as happened during COVID under the Slow Streets initiative, without waiting for the city to take action. “We’d have to rely on residents to make safe decisions,” said Ellis, “and it also brings up the question: can you do traffic calming everywhere at once?”

“From the city’s perspective,” Grigoraitis added, “we have to be looking at every street in the city. When we get into ‘my street,’ ‘my street,’ ‘my street,’ we also know that there can be unintended consequences,” such as the possibility that adding traffic calming measures to one street might cause drivers to cut through using a different street. “We welcome feedback and concerns, but we really want to be looking holistically about how we’re implementing measures. And strictly from a liability perspective, we really don’t want people engaging in their own infrastructure improvements.”

The intersection of West Wyoming Avenue and Berwick Street, where a fatal collision took place in 2018. The DPW added an island to make the crosswalk safer for pedestrians, but too many vehicles struggled to make the turn around it, said DPW Director Ellis, so it has since been removed.

Ellis added, “This is something we hear a lot: ‘We want to keep the traffic on the main roads, keep the traffic off the side streets.’ At the end of the day, every street in Melrose is basically a residential street. We don’t have big commercial strips. Even downtown, we have people living upstairs. Everyone needs to keep in mind, when we’re talking about speeds and safety and cut throughs and everything, every street is somebody’s street.”

In a separate conversation, Ped-Bike Chair Nelson reflected on the role of the Ped-Bike Committee, which is a volunteer group filled with residents who are passionate about street safety, including some residents who have day jobs in planning and engineering.

“Regular people in Melrose have gotten so mad about certain intersections,” she said, “and we’ve been trying to bring people’s voices together to elevate those for the city, to help the city see what people want.”

The lack of a clear process for making specific safety improvements has been frustrating for many members, Nelson continued. “If someone is worried about safety, everyone is randomly emailing people. People are voicing their concerns, and the city just says, ‘we need to do a study.’ If no one’s died there, they’re not going to do anything, because almost-collisions won’t be captured in the data. It feels like a dead end a lot of times, and we keep saying the same things.”

Members of the Ped-Bike Committee are optimistic about the Vision Zero Task Force as a way to bring up these issues with the city and have them taken seriously. “We are looking forward to working with the city,” added Nelson, “and we especially appreciate the mayor's commitment to Vision Zero” as the first mayor to make Vision Zero part of her platform.

But, Nelson cautioned, if the process takes too long, the consequences could be dire. “It only takes one person dying,” she emphasized, “and you will be on the record as not having done enough to prevent it.”

Follow Us: